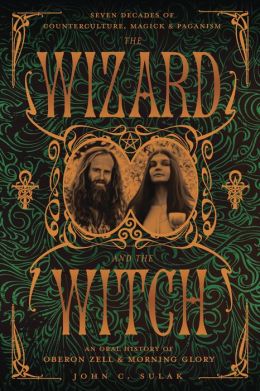

Open, honest and radical in tone, The Wizard and the Witch captures interviews with Church of All Worlds founders Oberon Zell and Morning Glory along with significant characters involved in their lives. As early members of the North American Pagan movement and ardent hippies, their offbeat lives captured public attention in manners both scandalous and benign well into the 1980s. From bringing mythical creatures to life to weathering community sex scandals, the Zells have shared a unique life worthy of documentation.

Archivist John Sulak engaged in exhaustive interviews then transferred from recording to book. In the process of these intensive interviews (an appended commentary from Llewellyn editor Elysia Gallo mentions that the original manuscript was more than 1500 pages) much is revealed about where witchcraft, Wicca and Paganism converges – and also where it parts ways.

Those interviewed for this history speak from a time when Pagan and Wiccan were not interchangeable terms – a time when a Wiccan was not another kind of Pagan. While what the Zells practiced via Church of All Worlds might be called “Wiccan” or “Wicca inspired” according to modern polytheists that have stepped outside Pagan culture, they state themselves that what they do and did is explicitly not Wiccan. Wiccan practices during the 1960s were completely different.

Several snippets shed light on topics of historic debate that still surface today. For example, Sulack comments in his narration, while giving context to the Zell’s friendship with Raymond Buckland: “[Gerald] Gardner’s claims were dubious even in 1971, and in the years since there has been abundant debate and research about where his tradition really came from.” It further clarifies that the Wiccans of the early 1970s were not rural hippies. “Like the characters of Bell, Book and Candle, they were urban witches and weren’t interested in a rural lifestyle.”

Yet, as readers know, eventually Paganism came to include Wicca and almost (but not quite all) any witchcraft that wanted a seat at the table. This may well be a result of the Zells’ influence on the Pagan movement, an influence that continued even during their decade of absence.

A frequent theme of this history is that of inclusion. The Church of All Worlds meant to be spiritually inclusive. Morning Glory and Oberon both reflect often on their inclusive attitudes in polyamory. In their touching memories about Morning Glory’s fundamentalist Christian mother Polly, it is clear that her inclusiveness expanded to Morning Glory and all of her lovers.

Oberon in particular speaks of the intentional inclusiveness of the Church of All Worlds, how it brought together all sexual identities, all types of Pagan-influenced spiritual practice and tradition. Morning Glory speaks of her own inclusiveness in the chain of polyamorous relationships and how that impacted her family.

Readers will find the raw honesty of this history striking. Admissions of bad parenting, mistakes in judgment and karma returning to roost weave between the many moments of wonder that the Zells have shared. There is also a setting straight of many an old record. The Zells have weathered multiple scandals, the dissolution and resurrection of the Church of All Worlds and are now passing through what an astrologer might call a second Saturn return, complete with menopause, death of a parent, and both experiencing cancer.

This is a book to read with personal agendas set aside because it may well be the single best historic account of Paganism’s evolution in the United States to date.

~ review by Diana Rajchel

Archivist/Editor: John C. Sulak

Llewellyn, 2014

pp. 410, $24.99