Does retelling ancient myths and folktales from a feminist perspective tell us something new about them? Aren’t the female characters in the stories constrained by the cultures of origin? Re-tellings cannot be entirely faithful to the source material because they are intended for a modern audience, with different needs, but they must respect the original stories, also. We need to avoid anachronism, particularly when speaking outside our own culture or dealing with the past. Retelling or re-imagining is not the same as historical fiction, a delicate line that Kris Spisak walks well – she has previously written a novel centered on the ideas of Baba Yaga, and here she retells a number of Russian folk tales in supple and elegant prose as well as giving a historical grounding in Russian culture, the Christianizing process that shaped the typical uses and meanings of these tales, and their roots in the ancient Trypillian and Scythian cultures.

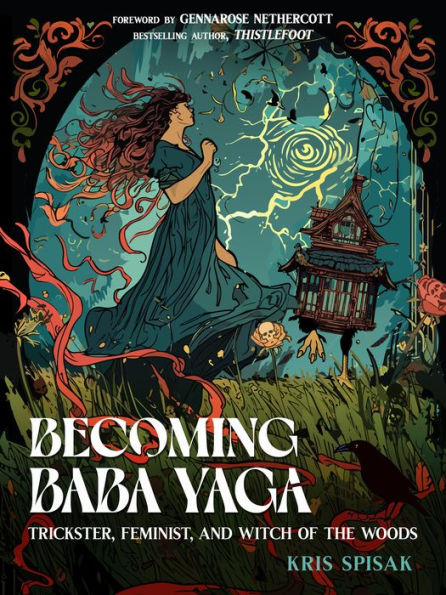

Baba Yaga is the Witch of the Woods, an old woman who lives in a small hut which walks on chicken legs, both a dangerous force when disrespected and a blessing power to the worthy traveller. She resembles other characters from European and world folklore and Spisak draws in similarities, including some from contemporary pop culture like Sonic the Hedgehog (!) and various wicked witches, but there is much more going on there.

Mythologies begin in particular landscapes and particular peoples, although themes drawn from the common human experiences cross these boundaries. Myth is history and culture, and retelling myth a living, breathing way of keeping culture alive and growing. A good retelling begins from the origin, explains and understands that place, then draws us past it.

Spisak’s book is a lush and very literary exploration, a real pleasure to read. She is solidly based in the archaeology and the folklore collections and adapts these stories to make them flow better in English, but not to lose their particularly Russian and Slavic character (although principally associated with Russia, Baba Yaga stories are also told in Ukraine, Poland, and Byelorussia). Spisak poses, in the retelling of these tales and her analysis of possible advice hidden in them, issues posed by them, the same question repeatedly; “have you come to do deeds or to run from them?” She sees the myths and stories as ways to not escape reality, but to reframe its issues and our response to them.

The chapters are each set up in the same way – she retells a story of Baba Yaga, generally a few pages long, and then she explores the questions posed in the tale and options for action coming from different answers. She ties the Baba Yaga back to an older stratum of mythology, to various goddesses in Russian and Slavic mythologies, to spirits of the forest and chthonic forces of death and rebirth. She paints the figure as quintessentially Slavic, epitomizing virtues of hope, pride, endurance, independence, and stubbornness. But she also specifically is a complex and powerful female force, a mentor to capable and confident women.

There is a great deal of fascinating discussion here and a fine collection of folk stories, a engaging introduction to Baba Yaga. And an excellent discussion of how folk tales can be used to improve our own lives, to explore conflicts and possibilities, to open up our eyes. I found the book engrossing as I am continuing to read more in Eastern European folklore, mythology and magic.

~ review by Samuel Wagar

Author: Kris Spisak

Red Wheel/Weiser, 2024

204 pg. Paperback £13 / $24 Can / $ 17 US