This is a book likely to appeal to some particular readerships: musicians, students of Japanese art and culture, practitioners of martial arts, and meditators interested in various disciplines of breath practice.

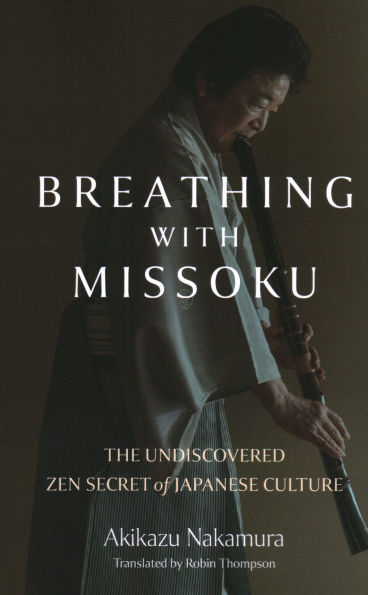

Author Akikazu Nakamura is a research chemist who became a world-renowned master of the Japanese bamboo flute called the shakuhachi. His new book (translated into English by Robin Thomspon) has been over 20 years in the making. He writes that when he first published it in Japan, his goal was “to reawaken a dormant tradition among the Japanese people,” who he says, through modernization over the last couple of centuries, have lost their traditional ways of breathing and moving in their bodies.

Missoku, or esoteric breathing, is a practice Nakamura came upon as he perfected his shakuhachi performance technique. The practice is said, also, to increase one’s powers of concentration while also giving one a sense of freedom. Nakamura gives detailed instructions and writes that missoku is completely different than breathing from the abdomen and chest as Western musicians do. Instead, missoku involves maintaining a pose with the abdomen extended slightly when both inhaling and exhaling. This allows shakuhachi masters like Nakamura to play the instrument continuously for long periods of time, taking deep breaths without tensing or moving the body, holding large amounts of air in a single breath.

Nakamura writes that he’d like to see Japanese people return to this ancient “culture of breath.” Because, he says, Japanese people have adopted the shallow abdominal breathing “prevalent in the West,” they have “unconsciously lost [their] sense of tranquility, of stability, of concentration and of strength.” To a non-Japanese reader, Nakamura comes across as a bit culturally chauvinistic.

One of his broader points is that attention to breath is central to Buddhism, though the missoku method of simultaneously inhaling and exhaling is not what was taught in the earliest forms of Buddhism. The earliest Buddhist scriptures, including the foundational Anapanasati Sutta, part of the Pali Canon--considered to be the closest rendition of what the Buddha taught, about 300 years before monks started writing the teachings down-- instruct meditators to inhale in short breaths and exhale slowly. That’s not missoku. Once Buddhism spread to Japan, the early Zen practitioners developed other breathing practices, including visualizing the breath and counting the breath.

Nakamura writes that the practice of missoku, which involves tilting the pelvis and extending the abdomen, “became most strongly advocated as a consequence of its use by a specific group of monks when they played the shakuhachi.” That’s because the shakuhachi is a particular type of wind instrument that requires one to have an unusual amount of breath. Training in the shakuhachi arose within a subsect of the Rinzai school of Zen, known as the Fuke sect, whose members were also part of the samurai warrior class.

I found it fascinating to consider missoku in light of what Nakamura summarizes: the historical interplays between social caste, military structure, religious sects, music, and physical culture.

~review by: Sara R. Diamond

Author: Akikazu Nakamura

O-Books, 2024

152 pp. $12.95