Decadent societies turn away from light and optimistic visions toward their dark undercurrents. This is the sludge usually buried and repressed, the lust for power, the urge to destroy (which Bakunin rightly described as the initial impulse of a creative urge toward social renewal). Perhaps like the canary in the coal mine the most sensitive – the artists, the mystics – connect most strongly to the spirit of the rising darkness. And so, the current interest in the Satanic / Luciferian / Lokian, in figures like the demon Lilith and the destroyer goddess Kali, in Santa Muerte, reflects the urge to destroy rising in Western culture like a dark sap from dying roots. Rather than building up, Western culture is tearing down and burning up whatever has been built in the past.

This urge is for destruction before renewal, let us hope, like the new growth after a forest fire.

We have been here before – the great wave of artistic and cultural Satanism in the 19th Century, the decadent and occultist wave of the 1920s, the punk movement in the 1980s. Now, where will we go from here? What will remain after we have burned it all down? And how can we avoid being swept with the currents of the dark permanently away from the light?

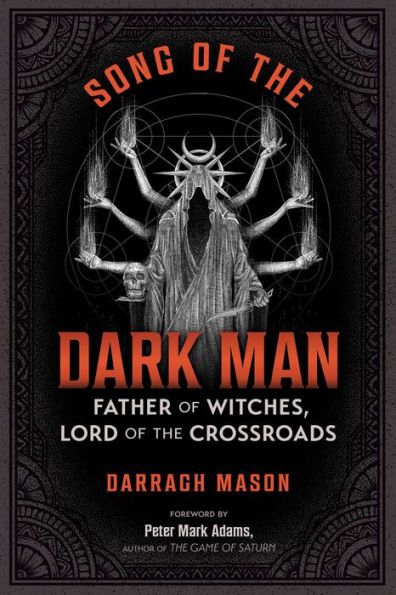

Song of the Dark Man explores the embodiment of the urge to destroy and recreate, the spirit sometimes called Lucifer, the Devil, the Dark Man. Mason begins with a general sketch of folklore and historical stories of the devil, the faeries, the daimon (depending on the culture of the person having the encounter), both modern influences though Robert Johnson the blues magician who sold his soul to the devil to master the blues, the djin in popular Islam. He retells some folktales from Ireland of Oisin and Finn, and of the challenging presence that one meets on the roads, then trickster stories. He leaps from place and time, Victorian England with ‘Spring-Heeled Jack’ (aka the Ripper), the strange 1855 path of cloven hooves in Devon, to ancient Ireland, to Pied Piper and Grimm folk stories, to the confessions of early modern witches.

Rather than presenting a continuing story or logical narrative Mason wishes to evoke an eerie mood and a series of impressions of an uncanny presence in the first half of the book. He does this through briefly retelling stories (many of which I had read in other places), with minimal context or analysis. The second half of the book, chapters 8 to 15, is a series of short firsthand accounts of encounters with the Dark Man from contemporary occultists interviewed by Mason.

The principal interest to me in the book was these firsthand encounters, although I wanted more depth – what changed for the people having these encounters? How are their lives different as a result? Overall, Mason's work doesn't do much to explain, direct, or inform the reader. There are much better books dealing with Victorian Satanism, with Irish folklore, with each of Mason's topics.

I will have to say, save your money and don’t buy this book.

~review by Samuel Wagar

Author: Darragh Mason

Destiny Books / Inner Traditions, 2024

187 pg. Paperback £13 / $24 Can / $17 US