Aleister Crowley published ten volumes of his journal, The Equinox, from 1909 to 1919. The published material includes A.: A.: laws, rituals, and rites, along with reviews and magical works by other practitioners. Very little of this has been reprinted, although these volumes are a treasure-trove of esoteric lore. Fortunately, these hundred-year old publications have been preserved by Crowley's successors and are being selectively restored in new editions.

As is evidenced in his writings on the tarot, Crowley's work on specific subjects was scattered all over the place – in his unpublished journals, in The Equinox, and in other books and magazines. Over the past few decades, Lon Milo DuQuette has patiently collated and annotated topically-related materials stored in the archives of the O.T.O. or the A.:A.: and republished them as coherent collections for the edification of students of the occult.

DuQuette states that “every magical ritual is a sacred drama.” Likewise, the theater is a kind of magic. Dramatic rituals were at the core of the ancient mystery religions. Make no mistake – Crowley didn't attempt to replicate or channel the ancient Eleusinian Mysteries! The content of the original Eleusinian rituals remains cloaked in obscurity, since no ancient writer ever dared to reveal them in writing. Even the gossip-mongering chatter-box Plutarch gave only tiny hints.

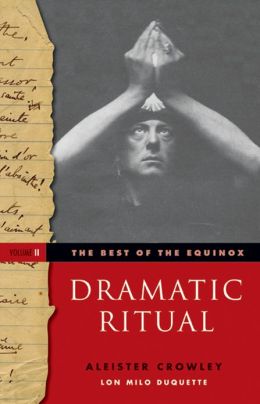

The Best of the Equinox, Volume I is dedicated to Enochian Magick. This second volume is focused on ritual, with Crowley's “Rites of Eleusis” as the centerpiece of the collection. The contents are not reproduced in their order of publication, but in an order designed to make sense to the reader. The essays “Of Dramatic Rituals,” “The Rites of Eleusis: Their Origin and Meaning,” and “Concerning Blasphemy in General and the Rites of Eleusis in Particular” are included. Of necessity, Liber 963 is reproduced, along with the violin score of “Thelema: A Tone Testament” by Leila Waddell. The short but lovely oration, “The Interpreter” and a longer invocation by Francis Bendick, “The Earth,” completes the collection. Rare photographs from the archives are scattered through the book.

Crowley revived the concept of the Eleusinian dramatic ritual for his own purposes, and then borrowed the title of Eleusis (the reason isn't entirely clear). His intention was to “induce profound changes in consciousness” in the participants. Crowley's ritual plays enact the powers and subsequent failings of the seven planets, from Saturn to the Moon, in the order of the descending Sephiroth.

The “Rite of Artemis” premiered on August 23, 1910 in London. It combined dance, poetry, and music, along with a Cup of Libation shared with audience members. Imbibing the potent hallucinogenic beverage undoubtedly enhanced their experience of the performance. After this success, Crowley staged the cycle of seven plays, “The Rites of Eleusis” through October and November 1910. Perhaps he wished to become the magickal (and financial) equivalent of the impresario Diaghalev and his Ballet Russe, who were at that time experiencing unrivaled success in Paris. The plays dramatize the descent of spirit into matter, and the return of matter to the spirit or godhead. The O. T. O. revived the rituals in the late 1970s, and they have been produced regularly ever since.

“The Rites of Eleusis” are formatted like a play, and begin with listing the dramatis personae and simple staging directions. Casts are small, from four to eight actors. The dialogs are supplemented with poems indicated by title (but not reproduced because of copyright restrictions). The titles of classical music selections used in the productions are given as footnotes. In addition, the stage directions include the performance of Thelemic rituals like the Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram that are found elsewhere (see: DuQuette, “The Magick of Aleister Crowley – Handbook of the Rituals of Thelema”, RW/W 1993, 2003).

Those who wish to produce the plays will need a copy of Swinburne's “Atalanta” and musicians capable of playing some fairly demanding works by Bach, Schumann, Brahms, Wagner, and others. The plays may seem brief in the text, but if performed with all of the referenced rituals, poetry, evocations, music, and choreography, each play could last an hour or more.

The full text of “Liber DCCCLXIII (963): The Treasure-House of Images,” starts at page 157. This includes affirmations for all twelve zodiac signs, the sun and moon and the remarkable 169 Cries of Adoration.

This collection provides an impressive display of Crowley's broad knowledge of mythology and esoteric associations with the planetary deities. References to Greek, Babylonian, and Egyptian myths are scattered throughout the works. The effusion of his poetry is equally impressive; like Shakespeare, much of the dramatic dialog is written in rhyming poetic meter. Reading through the dramas silently gives only the faintest impression a full production would make on the audience. Perhaps someday the O.T.O. will film their productions and offer the collection on a DVD.

In “Concerning Blasphemy in General and the Rites of Eleusis in Particular” (page 135) the reader is treated to Crowley's perpetually entertaining, biting sarcasm as he lambasts the critics who must have complained about his “heretical” or “atheistic” productions. He points out that teaching religion by dry rote bores students into a coma, while teaching through dramatic ritual instills ardent enthusiasm.

This is an enormously valuable addition to the Crowley literature that's in-print. It is finely organized and formatted. We denizens of the esoteric world owe a debt of gratitude to Mr. DuQuette for his years of dedication to this labor of love. Recommended to Crowley students and those who wish to examine early 20th century examples of dramatic ritual.

~review by Elizabeth Hazel

Author: Aleister Crowley

Introduction by Lon Milo DuQuette

1912 Ordo Templi Orientis/ 2013 Red Wheel/Weiser

pp. 234 $18.95